Like the vast majority of white Americans I’ve been numb to my white privilege for most of my life.

As a progressive thinker and activist, I never thought of myself as racist—that is until the Black Lives Matter Movement challenged whites to examine their privilege, publishing article after article highlighting our bubble. It’s impossible to avoid these writings. They keep popping up on my Facebook page and in the progressive blogs I follow like, Blackgirlinmaine and Medium.

The more I read the more I realize I have a lot of work ahead of me in examining my history of white privilege. (I recognize that low income whites by virtue of their economic status don’t have the same reaction to white privilege. Being poor makes them feel anything but privileged.)

As I set about deconstructing my internalized racism, I time traveled to my 1950’s formative years in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. My upper-middle-class family consisted of two younger brothers, an attorney father and a homemaker mother. Black and whites lived in separate parts of the city. I went to public schools where I was in accelerated classes, which were 90% white in spite of the large black enrollment.

Yours truly, the summer before 7th grade

My first awareness of racial barriers occurred in 7th grade.

The one black student in my class was a bright, friendly girl named Tammy, who always sat in front of me because seating was alphabetized according to last names. Her last name was Ewell and mine was First. We checked our homework together and often ate lunch together.

One day I asked Tammy if she’d like to come home with me after school. She drew back, and after a silence, answered, “I’m not sure that’s a good idea.” I didn’t press her for an explanation. I took in her answer and speculated that she was protecting herself against any discomfort she might feel from my mother’s reaction.

Fast forward to high school. The summer before my senior year I was invited by a Quaker family to travel with them to a peace conference where Martin Luther King spoke. I was very moved by him. That fall when I returned to my all-girls’ prep school, I wrote an article in the school newspaper about King, expressing admiration for him.

The Southern girls came after me, telling me how evil King was. They never spoke to me after that. This was my first direct encounter with white hatred of blacks.

A few of the books written by the prolific bell hooks

In the 1990’s I was part of a women’s book group that decided to read bell hooks’ works. Someone suggested we invite a black woman to join us to help us understand hooks. When the black woman was invited, she declared, “I’m not going to do your work for you.” Another epiphany.

In working to unpack my white privilege I’ve been enlightened by Peggy McIntosh’s essay, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” McIntosh has created a list of 50 fundamental ways that whites benefit from white privilege on a daily basis.

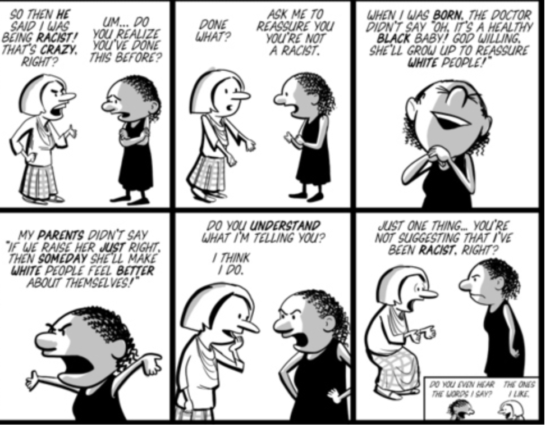

The way white privilege appears to many people of color

The list runs the gamut from the freedom to choose where to live, where to shop, where to travel, but most eye-opening were the observations: “I do not have to educate my children to be aware of systemic racism for their own daily protection,” or ‘I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.”

The blog radical copyeditor.com offers this take on white supremacy: “It’s the water most white people swim through without realizing they are wet. It’s the basic fact of U.S. culture and everyday life and a foundational truth of this country.”

Gathering for the Women’s March, Jan. 2017; critics called it an example of white privilege

While reading is crucial towards expanding my awareness, I’ve begun to realize that it can be just as valuable to watch myself on a daily basis, taking note of all the opportunities I take for granted that are regularly denied people of color.

I look around in my favorite coffee houses, eateries, and my neighborhood, noticing how white they are, and wondering what it would be like if people of color inhabited these same spaces in large numbers. How would the dynamics change? Would there be subtle pressures to keep people of color away?

Calling out white privilege