For most Americans the Vietnam War has been reduced to a historical footnote. For those who served, it is not easily forgotten. Many Vietnam vets continue to suffer from PTSD or, for the truly unlucky, from crippling wounds or from Agent Orange.

Other vets, like Peggy Akers of Portland, Maine, bemoan the fact that the lessons of Vietnam continue to be overlooked as we plunge into one senseless war after another.

Peggy, now 71, enlisted in the Army at the age of 20, won over by the Army’s offer to pay for her education. She had completed two years of nurse’s training at Columbia University, but welcomed the chance to receive her remaining college education free. At Columbia she protested the war by hanging anti-war banners from her dorm window. As an Army nurse she envisioned doing good work without having to identify with the war’s philosophy.

Army nursing was grueling with 12-hour shifts leaving little time for anything but sleep and meals. Peggy went the extra mile for her patients. She would drag patients’ beds to the ward’s front desk where a ham radio was connected, allowing for young homesick patients to talk to their families back home. She spoke movingly of comforting soldiers who were badly shaken after receiving “Dear John letters”—an all too common occurrence.

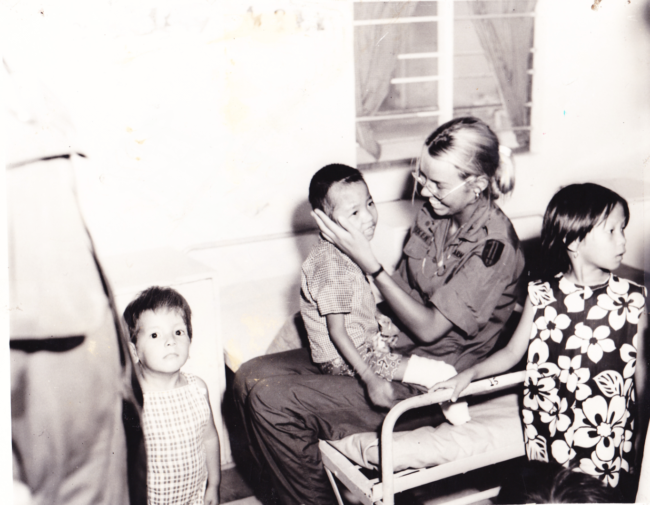

Peggy, whose soft-spoken manner belies a rebellious streak, bucked the rules and snuck Vietnamese mothers into the unit where their children were hospitalized for wounds from Napalm and land mines. Peggy gave into the mothers’ pleas to sleep under their children’s beds so they could be close to them.

In another act of rebellion Peggy recalled the time she and a like-minded nurse attended a USO event with a lot of top brass in attendance. Peggy and her accomplice slipped into the coatroom, gathered up all the officers’ hats, put them in a large plastic bag, took them outside where they dug a hole and burned them.

Justifying her action Peggy told me: We . . . took the hats as it was our only way to protest the high-ranking officers ability to send these beautiful young men to the field to die or to be forever maimed.

In spite of her quiet acts of rebellion and to her great surprise, Peggy was awarded the Bronze Star. It was around the time her tour was ending. She was summoned into a general’s office where she found herself surrounded by officers with medal-encrusted uniforms. Peggy couldn’t figure out why she was there until they pinned the Bronze Star on her. To this day she doesn’t know why it was awarded to her. During the Iraq war when many Vietnam vets were protesting the Iraq war by throwing their medals over the White House fence or returning them, Peggy returned her Bronze Star.

When her tour was over and Peggy returned home, she felt a huge disconnect between her life in Vietnam and that of her neighbors who went about their days, engaged in routine activities like going to work, shopping, or meeting a friend for coffee. Consequently she didn’t tell many people she had served in Vietnam, “stuffing it,” in the spirit of other returning vets who felt similarly alienated.

After seeing so much loss of life in Vietnam Peggy thinks of the Vietnamese and our “enemies” everywhere as “people just like us,” who deserve to live in a peaceful world. She found a home for her anti-war views in Vets for Peace, which she joined in the 1980’s. Peggy continues to march in anti-war protests with Vets for Peace in her home state of Maine and across the country.

As a member of the Vets for Peace Speakers Alliance Peggy frequently paired with another vet, giving talks in local high schools where they described their time in Vietnam, while being careful not to proselytize. These talks proved very popular, but the invitations all but dried up when Bush, in the aftermath of attacking Iraq, insisted, “You’re either with us or against us.”

Peggy today: note the Quan Yin, Goddess of Compassion, statue over her shoulder–this was not staged!

Peggy is a local organizer for the upcoming Vets for Peace My Lai traveling photographic exhibit designed to mark the 50thadventure of the My Lai massacre. The exhibit will be installed at Portland’s Media Center on September 14thand 15th. The exhibit and two day events are designed to honor the Vietnamese civilians who died in the American war.

The “My Lai Memorial Exhibit” will feature a poetry reading by Vietnam veterans where Peggy will read her poem, “Dear America,” which she wrote soon after returning from her tour in Vietnam. Her poem ends with these words:

America you never told me that I’d put so many of your sons, the boys next door in body bags. You never told me . . .