I grew up in the 1950’s when gender roles were strictly defined. My mother, like most women of the era, stayed at home, focusing on creating the perfect home and perfect children. My father, like Don Draper in “Mad Men,” spent long hours at the office, mainly seeing his kids at the dinner table and on weekends, when he wasn’t catching up on work or playing tennis.

The popular ’50’s TV show, “Father Knows Best,” perpetuated the image of a family ruled by the father.

My father competed intensely with my two younger brothers, hating to lose even a game of paddle tennis with them, slamming down his paddle and storming off. The least little thing could provoke my father, like not having chili sauce for his meatloaf, prompting him to bolt from the dining room table, slamming doors in his path.

Like the rest of the family, I tried not to trigger my father, but he had a soft spot for me, his only daughter. I loved to read, spending summers with my nose in a book. Observing my love of books, my father frequently passed along novels he thought I might like. I remember reading “The Tin Drum,” not fully comprehending it, yet not daring to admit this.

During my middle school years my father dispensed advice when I became an editor of the school paper or when I was preparing a speech. But he fell short when I performed in school plays, always too busy at work to attend my performances. I learned to be grateful for what fathering was doled out.

Growing up, my mother took me into her confidence, informing me of my father’s numerous affairs. I can sill remember the time when I was 15, alone with my father in the car, running an errand. I worked up the courage to confront him about his affairs, which he promptly denied.

I would defend my mother against my father’s ridicule of her. He had a habit of mocking my mother when she made an intelligent comment, saying, “Jane, you’re not as dumb as you look.” I would jump to my mother’s defense, protesting he shouldn’t demean her. In response my father would laugh and say, “I was only joking.”

I can track my bad choices in men to my father’s model. I married a womanizer and was in a long-term relationship with a man who was verbally abusive. My father’s patriarchal behavior fueled the feminism I embraced later in life.

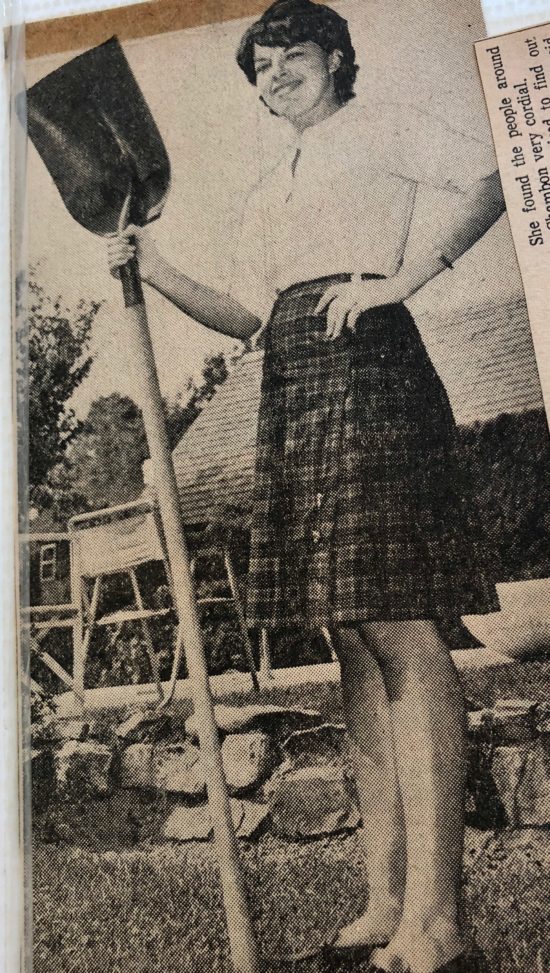

On the plus side my father rewarded my adventuresome spirit. During my sophomore year of college, I bugged him to spend a summer in Europe. He relented on the condition that I make it an educational experience. He helped me track down a work camp in Chambon, France.

My father assumed my future would consist of being a wife and mother. I had other dreams in mind, like graduate school. When I earned a full scholarship to Catholic University’s Social Work School, by way of a rare apology, my father confessed to misjudging me, accepting my idealistic desire to make a difference in the world.

My father lived by the dictum, “Persistence is the better part of change,” always keeping his goal in mind and refusing to give up. I took his lesson to heart, staying the course, when I pitched the idea for a column to the Syracuse Newspapers and later to the Syracuse NPR station for a women’s radio show.

I’m pleased to see new generations of fathers move from the sidelines into an active parenting role with their daughters and sons. Hopefully, they are breaking the chain of absent, tyrannical fathers.