I feel like I’m living inside the song, “Stop the World I Want to Get Off,” as I reel from our climate crisis, Afghanistan’s unraveling and a new Covid surge. Mary Oliver to the rescue! I pull one of her poetry books from my shelf, find a quiet place to stretch out and start to read. Oliver’s poems are balm for my soul. They settle me. I’m not alone. Many of my friends hold Mary Oliver close to their hearts as well.

Oliver’s popularity rests on poems that offer words to live by–words that stir our very being, like these verses from When Death Comes, that are tacked on the bulletin board by my desk:

When it’s over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it is over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

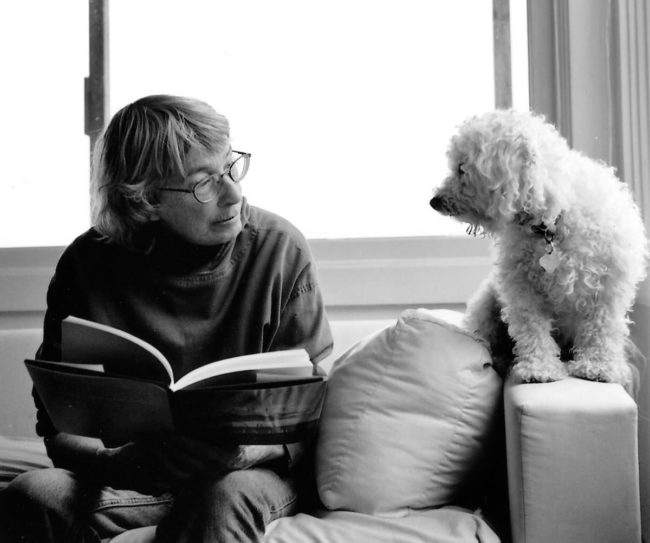

Oliver’s persistent subject matter is the natural world. Perhaps it’s her deep communion with nature that is responsible for her reverence for life. Oliver, who died in 2019 at age 83, was an introvert who thrived on solitude. She was most at home in the woods or by the sea, quietly soaking in the lessons provided by the trees, animals and sea life. When she walked the woods in Provincetown she had a habit of leaving pencils in trees so she could write down thoughts that surfaced during her walks.

An Oliver practice is to study nature and project her observations onto human behavior, as illustrated by the following excerpt from Wild Geese:

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

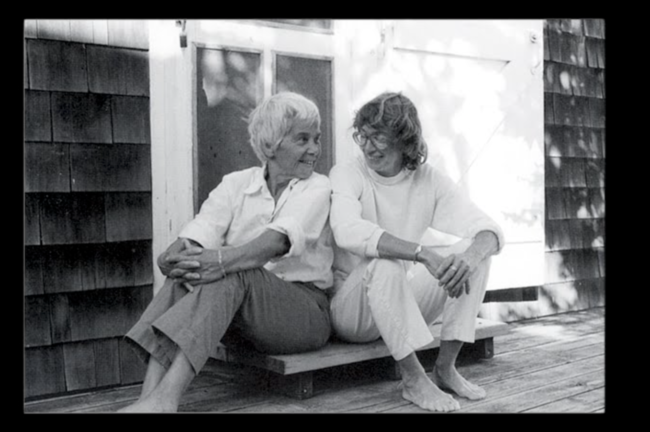

While Oliver seemed to posses an inexhaustible supply of poems about nature, she also wrote about domestic life. Particularly compelling are her writings on loss and grief in the collection, Thirst, dedicated to Molly Malone Cook, Oliver’s partner of 40 years, who died of cancer in 2005. In A Pretty Song, Oliver distills love and loss to its essence:

From the complications of loving you

I think there is no end or return.

No answer, no coming out of it.

Which is the only way to love, isn’t it?

This isn’t a playground, this is

earth, our heaven, for a while.

Therefore I have given precedence

to all my sudden, sullen, dark moods

that hold you in the center of my world.

Unlike female poets of her generation, such as Alice Walker or Marge Piercy, whose poems are full of feminist references to tackling the patriarchy, Oliver was apolitical, possibly to preserve her privacy. Writing without controversy kept her safe from unwanted queries from the press or public.

I find reading Mary Oliver infectious. As she pulls me into her private world of sturdy trees, the surf and friendly animals, I feel becalmed, wanting to spend time in nature, wanting to hone my patience to see more, to learn more.

Oliver’s last book of poetry, Devotions, is a collection of earlier works, including The Gift, which offers a gentle, loving commentary on aging:

Oliver’s last book of poetry, Devotions, is a collection of earlier works, including The Gift, which offers a gentle, loving commentary on aging:

Be still, my soul, and steadfast.

Earth and heaven both are still watching

though time is draining from the clock

and your walk, that was confident and quick,

has become slow.

So, be slow if you must, but let

the heart still play its true part.

Love still as once you loved, deeply

and without patience. Let God and the world

know you are grateful.

That the gift has been given.