I’m very clear that I want to grow old differently from the old lady personas adopted by many of our grandmothers and mothers, who donned polka dot dresses, dispensed little candies from their pocket books, and smiled demurely while keeping their opinions to themselves. Nor do I want to grow old having succumbed to plastic surgery to peel years off my face, or through any other measure to fudge my maturity.

I want to be anything but a ‘sweet little old lady.’ I want to be outrageous when the mood strikes me, kicking up my heels, and unafraid to state my beliefs.

Ann Tracy, A Free-Spirited Artist

It’s not always easy. While I’m a modern grandmother who stands in protest lines in all kinds of weather and travels to exotic places, the culture still has me in its grip. Every time I look in the mirror and find my jaw line sagging another few millimeters, or gaze enviously at the poses of the younger women in my Pilates class, recognizing I can no longer stretch and bend the way they do, I get a little discouraged.

In search of help to adjust my thinking, I googled readings that validate older women. “Learning to be Old” by Margaret Cruikshank was the perfect ticket.

According to Cruikshank, the first step to becoming the new, freed-up old woman is to “break out of the confines of youthful adaptation.”

In other words, we have to resist the cultural pressure that devalues older women who look their ages and not to feel inferior if we haven’t gone under the knife a zillion times like 77 year old Jane Fonda.

The joys of learning never have to stop.

We must give ourselves permission to like our aging bodies, dress however we like, and to speak our truths.

Cruikshank describes how old men’s face are valued for their lines of experience and wisdom, while old women’s faces are most valued when they remain the same as their younger selves, free of character lines.

How do we conquer these persistent stereotypes? How do we empower ourselves the way our younger selves did during the second wave of Feminism? One way is for older women to resurrect the consciousness-raising groups of our early feminist years, gathering in one another’s living rooms to deconstruct the sexism and ageism in our lives, and to support one another in the often lonely journey of aging as an older woman.

We have to transcend the message that once a woman “looses her looks” (a damning phrase if there ever was one—instead, how about once a “woman’s face matures”) she’s worthless.

One strategy is to take inspiration from those remarkable older women we know personally and those we read about—women who have aged with dignity and courage and backbone.

In the state of Maine, where I live, it’s almost impossible not to run into powerful old women who live alone in the country, lug their own firewood and shovel their snowy roads in winter, or old women in my city of Portland who wouldn’t miss an activist demonstration or cultural lecture. These women are easy to spot; they emanate self-confidence, humor and delight in being alive.

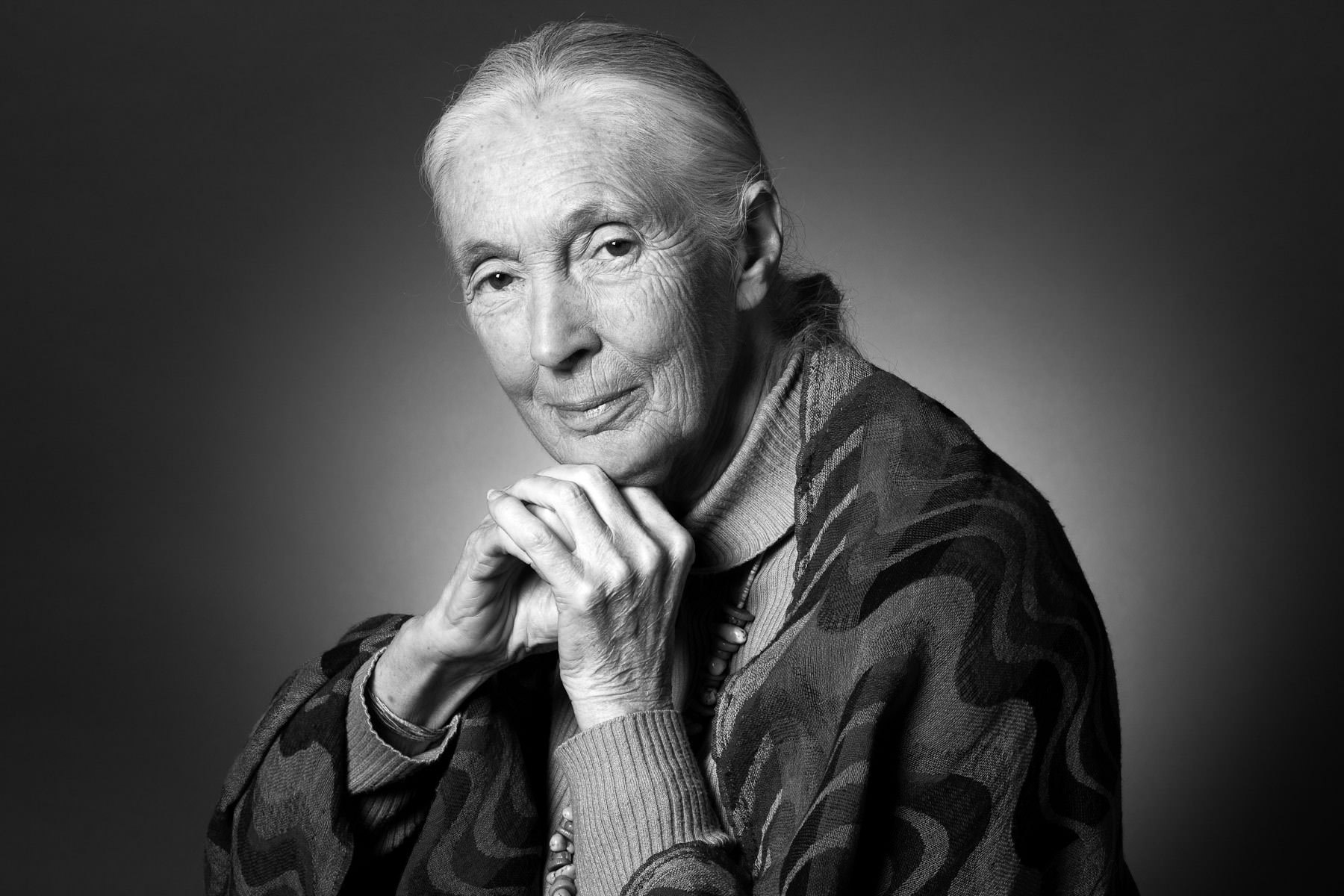

On my short list of women who have aged with grace are the famous ones: Jane Goodall, the late Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Mary Catherine Bateson and, the not famous: my Great Aunt Pearl, who took a solo trip around the world when she was 80.

Jane Goodall at 81–“There are more important things than how you look.” (billmoyers.com)

Come up with your own list. Jot down memorable words of your favorite wise old women. Keep this list front and center on your desk or bureau for inspiration. And, who knows maybe someday a younger woman will put you on her list!