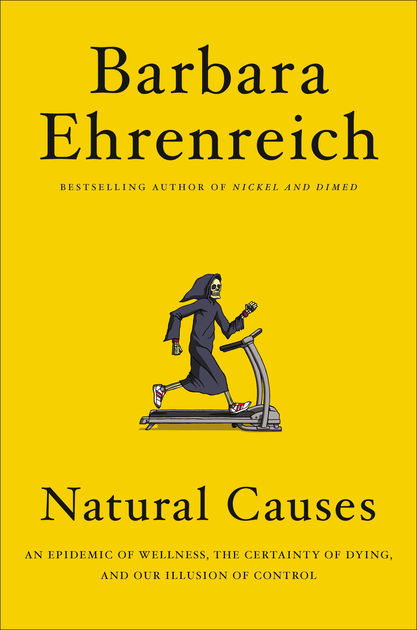

It seems like a paradox to accuse the wellness industry of adding stress to the lives of older Americans, yet this is a central thesis in Barbara Ehrenreich’s new book, Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, The Uncertainty of Dying and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer.

Ehrenreich maintains that many older Americans are stressed-out in their allegiance to “successful aging,” where old age becomes a battle to keep death at bay as long as possible.

In contemporary America death is treated as a disease rather than a normal stage in the life cycle. This adversarial relationship with death promotes a demanding wellness regime as the solution to longevity. To live longer older Americans are ingesting mega vitamins, eating bland healthy food, exercising like mad and succumbing to unnecessary tests pushed by our for-profit medical profession.

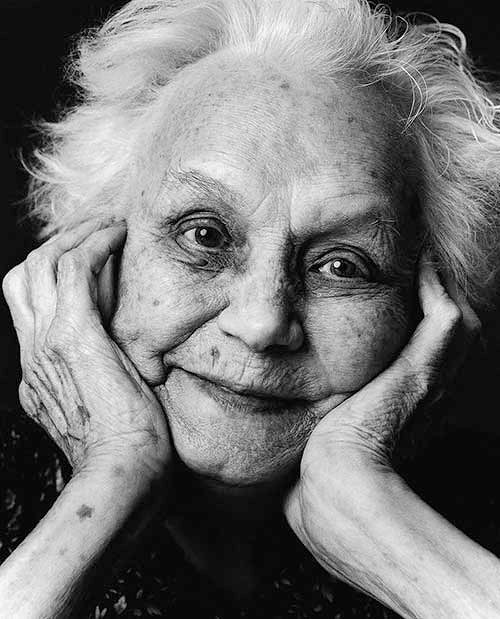

Ehrenreich, age 76 parts company with convention in her refusal to undergo annual physicals and routine tests like mammograms and bone density, insisting there is little proof for the efficacy of routine screenings which can raise alarm unnecessarily.

When her recent bone density test revealed that she had osteopenia or minimal bone loss, Ehrenreich’s reaction was, “What woman over 70 doesn’t have bone loss?”

She takes aim at the pharmaceutical industry that profits from early detection, frequently peddling drugs with questionable results. Fosamax, commonly prescribed for bone density, has been found to have serious side effects, including the possibility of fractures!

Ehrenreich maintains that she’d rather spend her ‘70’s and ‘80’s at her desk writing or taking a long walk as opposed to countless hours in a windowless doctor’s waiting room. She has a gym membership and eats healthy but not to the point of depriving herself of her favorite foods like butter, commenting, “What’s the point of toast without butter?”

With a Ph.D in cellular immunology Ehrenreich takes aim at the popular concept that positive thinking can defeat bad cells and that the right mindset can defeat our biology. She makes the case that cells and subatomic particles don’t have personalities; they go their own way regardless of how we react.

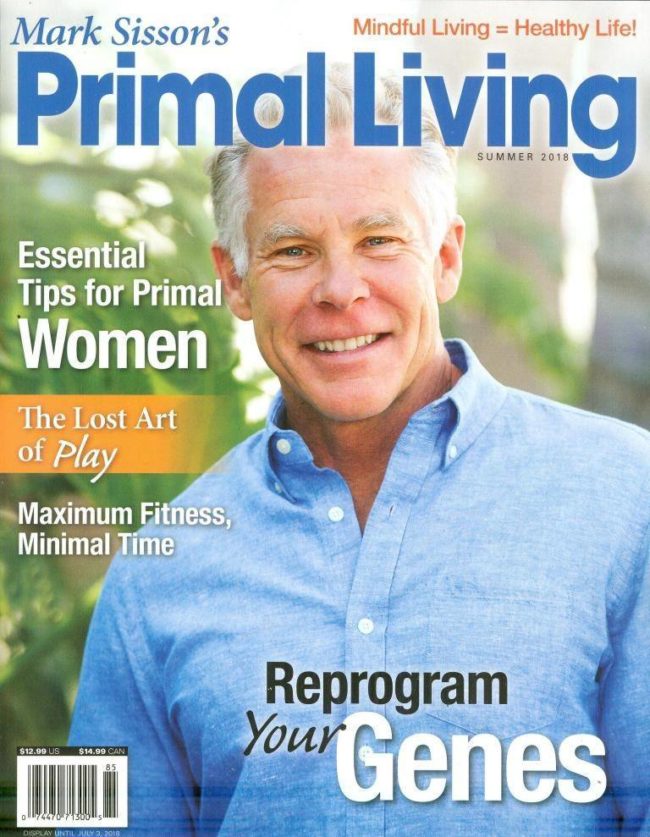

This wellness magazine promotes the article “Reprogram Your Genes,” a practice at odds with Ehrenreich’s findings.

I was reminded of a friend who, after being diagnosed with breast cancer attended a support group where she was encouraged to imagine friendly warrior cells attacking her cancer cells. When this didn’t prove effective she confessed to feeling like a failure. I can only imagine the vast number of women, like my friend, who were made to feel guilty for not imagining away their cancer.

In an interview with Slate to promote her book Ehrenreich suggests that the obsession with successful aging carries a strong level of narcissism. She told the interviewer: “It’s all about controlling what’s within the perimeter of your skin. It’s not about actually doing anything in the world or with other people.”

Successful aging is another benchmark that divides the privileged from the poor. It takes money to afford a gym membership, expensive organic foods, vitamins and medical screening procedures often not covered by insurance.

Pondering the wellness campaign to outwit death Ehrenreich writes:

You can think of death bitterly and with resignation . . . and take every possible measure to postpone it. Or, more realistically, you can think of life as an interruption of an eternity of personal nonexistence, and see it as an opportunity to observe and interact with the living, ever surprising world around us.