“Viewing art is the closest we can get to the core of life . . . Art represents the essence of what it means to be alive. Art transforms us.”

—Sarah Bouchard, Gallery Owner

“Art makes my life better. I see art everywhere I look . . . not just in paintings but in food, in flowers. . . We have always needed art to make our lives beautiful where we live. This impulse goes all the way back to the early cave paintings.”

—Josefine Auslender, Artist

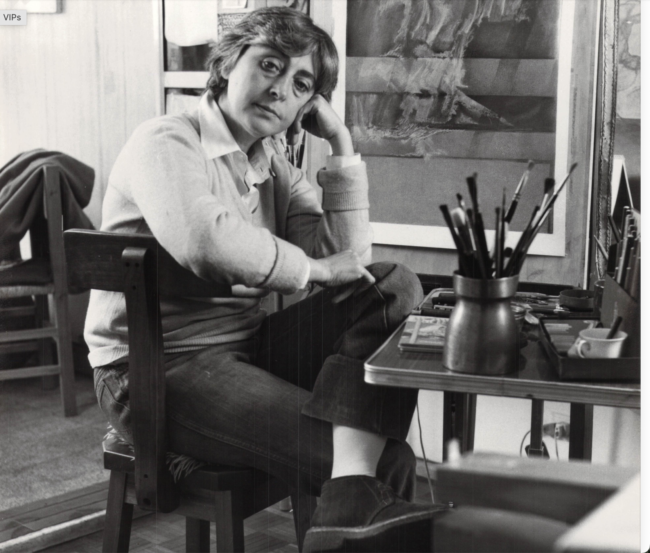

I was privileged to sit down with Sarah and Josefine in Sarah’s Woolwich, Maine gallery, where we were surrounded by the solo exhibit of Josefina’s art. I was there to interview Sarah and Josefine on the role art plays in our lives.

Opening the door to Sarah’s gallery delivered me to a magical space. I was transported by Josefine’s powerful images and by the serene woodsy setting, where majestic leafy trees are visible from the windows that flood the gallery with natural light.

Josefine’s art felt enhanced by the gallery’s setting. I wondered if her images were hanging in an urban gallery, if they would feel as sacred as they do here.

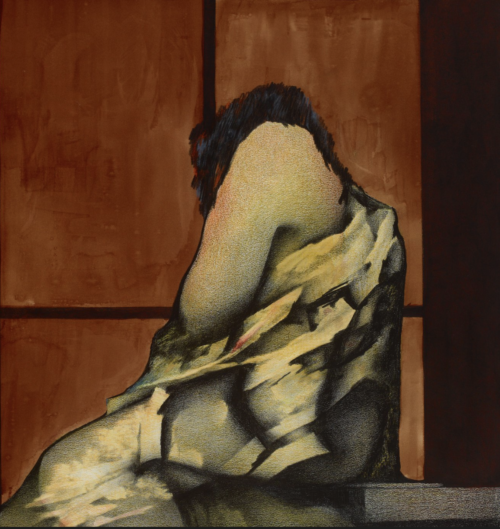

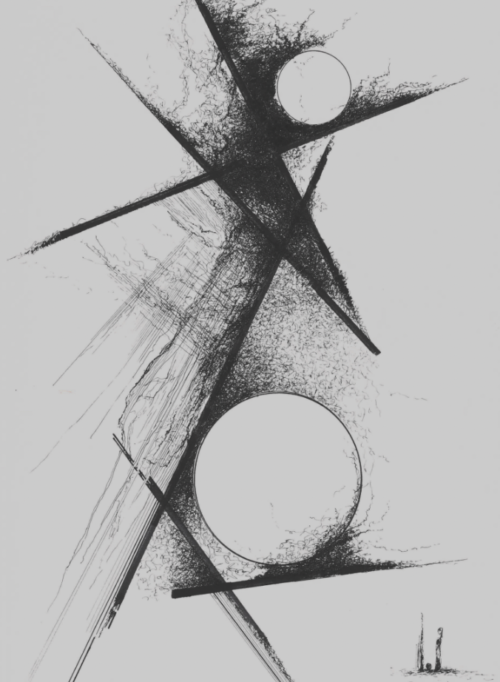

I had met Sarah before, but not Josefine. Sarah had described 88-year-old Josefine as a “spit fire.” Josefine didn’t disappoint. She smiled warmly, and talked passionately when she discussed the exhibit, which is grouped into two different periods in her life. The bulk of the show features abstract images of anguished mothers, painted by Josefine during the period she lived in Buenos Aires, when the “Dirty War” loomed.

Josefine’s father had moved his Jewish family to Buenos Aires from Germany during World War ll to escape Hitler’s persecution of the Jews. Josefine attended art school in Buenos Aires, where she continued to live after she married, enjoying a happy family life with her husband and two sons.

Josefine’s peaceful existence was disrupted in the late ‘70’s when a military junta took over the country, instituting a ruthless campaign to remove all dissidents, largely young people who “disappeared.” At the time Josefine’s sons were the ages of those who were disappearing.

Living in this tense political climate, impacted Josephine’s art. She relates being taken aback when dark images of women suddenly erupted in her work. She destroyed the first of these because “I was afraid of them.”

When these images kept coming, Josefine’s mentor encouraged her, not to fight them, but to let them out. She complied, baffled over their relentless appearance, commenting, “I felt like a medium.”

The “Dirty War” images of women pulled at my heart strings. When I first read about the “Dirty War,” I was appalled, but Josefine’s paintings left me experiencing the mothers’ pain at a deeper level.

Sarah articulated my response when she commented that “art allows us to deal with complex emotions and to understand ourselves better,” suggesting that art has the power to change us.

“The Blue Woman,” from the Dirty War series, where the images are depicted looking out the window, waiting for their children.