In honor of this year’s Women’s History Month, on March 11, 2018 the New York Times made a move to correct their longstanding emphasis on male accomplishments by publishing a special supplement entitled, “Overlooked.” This section celebrates 12 women of achievement who never made it into the Times obituary pages.

I welcome the Times “better late than never” effort, but it carries a cautionary note. As long as women’s history celebrations limit their scope to outstanding individual women, cultural icons like Sylvia Plath or Diana Arbus, we lose sight of the importance of popular women’s movements. It’s ordinary women banding together that have changed history.

While contemporary women recognize the importance of building movements, like #metoo, we don’t always step back to study how feminist movements throughout history have made a difference and to absorb the lessons of our foremothers.

American women tend to possess a limited historical perspective.

Most of us are vaguely familiar with the Suffragettes, crediting them with gaining the vote for women, but few women know the extent of the Suffragettes’ commitment, like being force-fed in prison and organizing on a mass scale through women’s newspapers that were distributed coast to coast, or the fact that it took decades and numerous setbacks before the vote was finally won. The latter fact bears remembering as feminists fight the abortion battle all over again.

Historian Gerda Lerner author of The Creation of Feminist Consciousness rolls back the clock as she examines women’s movements that challenged patriarchy.

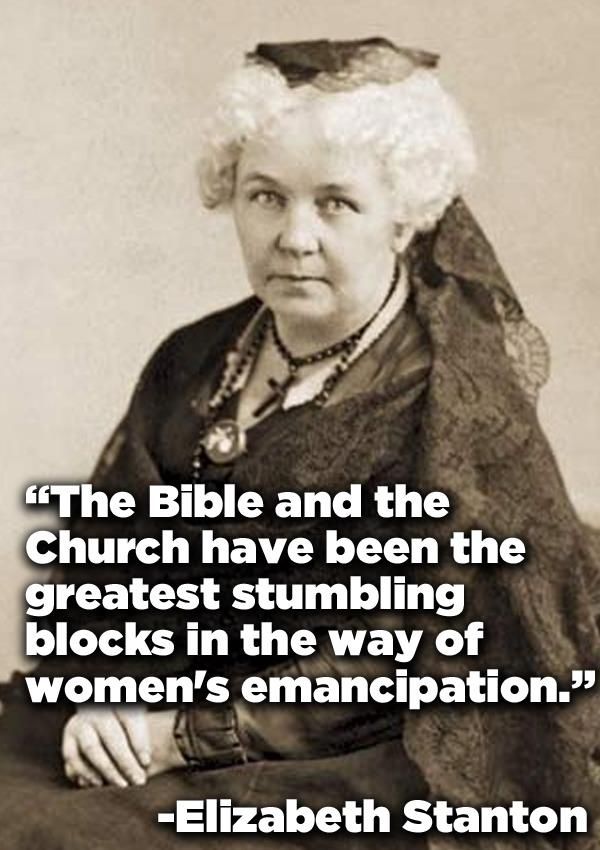

Lerner discovered that successful movements took on the prevailing cultural and religious issues of the times that held women back. For example, in the 19th century the Bible, just like today, was a primary source for defending male superiority and female submission.

In 1838 Sarah Grimke, a Quaker and abolitionist published a feminist version of the Bible where she interpreted the fall as showing Adam and Eve equally guilty, challenging the view that Eve was Adam’s subordinate. I can only imagine the rancor that ensued when Grimke wrote that the Biblical interpretation of the sexes was “no more than an arbitrary opinion.”

A few years later in 1895 the Suffragettes Matilda Gage and Elizabeth Cady Stanton published their version of Biblical criticism, The Women’s Bible. This was a work by committee where 26 women went through the Bible and struck out all references to male domination and female subordination. When I mentioned this to a friend she asked, “What was left?”

Feminist theologians of all faiths continue to struggle for female equality. While progress has been made some battles endure. Increasingly women lead congregations in the Christian and Jewish faiths. The Episcopal Church admitted women to the priesthood in 1977, but the Catholic Church continues to reject women for the priesthood.

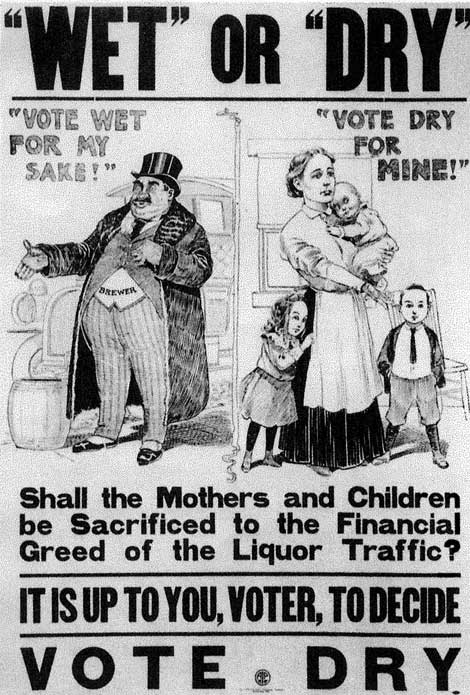

The Women’s Temperance League was another women-led movement from the 19th century. One popular view depicts the WTL as a group of prudish women who objected to alcohol out of their piety. In reality the WTL was a response to men drinking away their paychecks, thereby depriving their wives and children of basic necessities.

Women mobilized successfully during the labor movement of the 1930’s, forming their own union, The International Ladies’ Garments’ Worker Union. They succeeded in achieving pay raises and better working conditions for their members. Today unions have been weakened by low memberships and government restrictions on their activities—another example of the uneven course of change. The recent successful strike by West Virginia teachers offers new hope for women-led strikes.

In her groundbreaking book, Toward a New Psychology of Women, Jean Baker Miller describes women as affiliative by nature, meaning women tend to find their voices and gain empowerment in the community of other women. This sentiment is powerfully expressed in Helen Reddy’s enduring 1972 song, “I am Woman:”

I am woman, hear me roar

In numbers too big to ignore