GUEST POST by PAMELA VALOIS

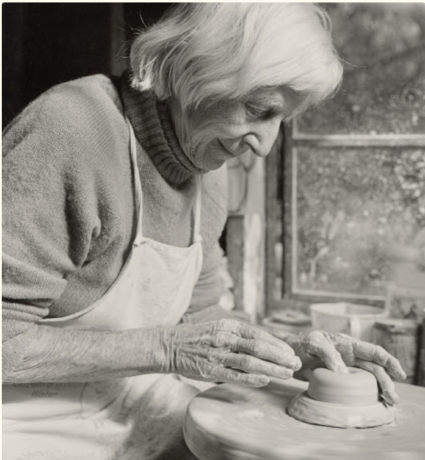

I met Jacomena Maybeck when I was thirty-seven and she was in her late seventies. She was tarring her roof, dressed in a halter top and shorts. I’d never met anyone like her. Our long friendship would help prepare me for my own winter years that I now find myself in, at age seventy-seven.

In her memoir, Jacomena wrote, “Here I am free of a job. Retired. Well, now what? What is there in myself to work with, to enjoy with? Really, age is a damn nuisance. You have to work harder for everything. But magic things still happen!”

For me, the magic is now living in Jacomena’s family home and savoring memories of her. But I realized that I didn’t know much about her early years, which formed and would support her as a widow and ceramic artist who lived a long and creative life until age ninety-five. For five years, I researched her diaries and letters and interviewed those who knew her. And finally, Blooming in Winter: The Story of a Remarkable Twentieth-Century Woman (She Writes Press, June 2021) will tell the story.

Jacomena had struggled to balance career, family life, and creative work. We agreed with Tillie Olsen whose book, Silences, was giving voice to the issue: “In motherhood, as it is structured, circumstances for sustained creation are almost impossible.”

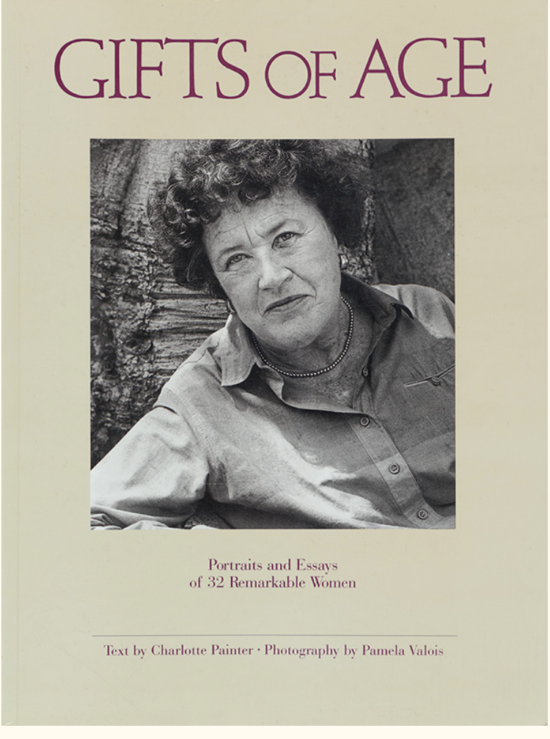

Jacomena urged me to hire a sitter for four hours a week to work only on “creative work.” Fascinated by how she and her friends lived, I interviewed and photographed them. I asked my friends whether they had an older woman in their lives and many answered that they wished for a mentor—someone who was thriving in “older age.” My collaborative project became a best-seller, Gifts of Age: Portraits and Essays of 32 Remarkable Women (Chronicle Books, 1985). Most of the women in the book were not famous, nor particularly talented, but they’d found new passions like writing, playing the violin, or acting in local theater.

Having a mentor, or just knowing a resilient older woman was invaluable in my forties.

Not only did Jacomena share her own concerns (like needing to build a railing for her “wobbly” friends), but she prepared me for this decade, the seventies, where health issues seem to take hold and widowhood is common, but many women are less burdened with career, children, and family responsibilities.

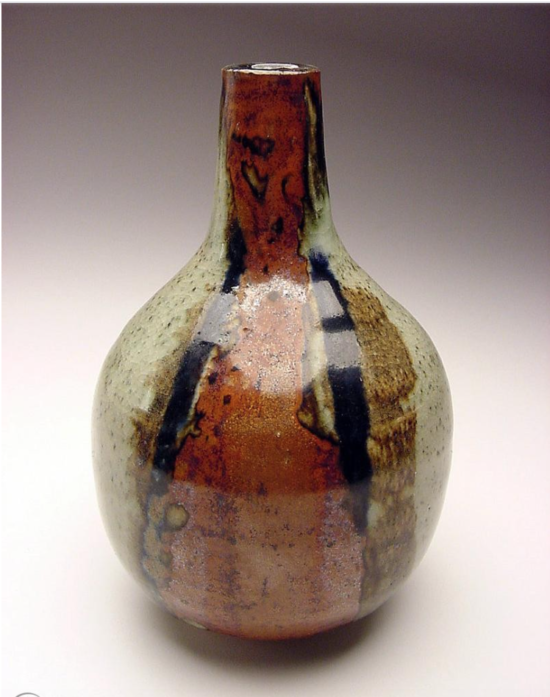

For Jacomena, a privilege of old age was that she could now make things just for herself—she no longer felt obligated to compete and make things that would look good in a ceramic exhibition.

“These days, I calibrate the work against the pleasure.” And facing early widowhood, she wrote, “These years are like a tree that began to put out little leaves and blossoms where before, it was a bare tree.”

Growing up in Sierra Madre, CA, Pamela Valois moved north to attend UC Berkeley during the Free Speech Movement. After almost flunking out due to political rallies, she returned to Los Angeles to become a dental hygienist. With a solid part-time job, she became a quasi-hippie, selling macramé and her photos at weekend craft fairs. Pamela got married on the lawn of Jacomena Maybeck’s Berkeley cottage and studied photography with Ruth Bernhard in San Francisco. Her first book “Gifts of Age” was published in 1985. “Blooming in Winter” is her second book.

Growing up in Sierra Madre, CA, Pamela Valois moved north to attend UC Berkeley during the Free Speech Movement. After almost flunking out due to political rallies, she returned to Los Angeles to become a dental hygienist. With a solid part-time job, she became a quasi-hippie, selling macramé and her photos at weekend craft fairs. Pamela got married on the lawn of Jacomena Maybeck’s Berkeley cottage and studied photography with Ruth Bernhard in San Francisco. Her first book “Gifts of Age” was published in 1985. “Blooming in Winter” is her second book.