Reading a 2017 essay by Deborah Tannen “My Mother Speaks Through Me,” I paused at the sentence:

Though my mother died in 2004, she is the one whose voice comes out when I speak, and whose speaking style shapes how I hear others’ words.

I too have been surprised, even amused, when I say something that sounds just like my mother. Unlike my younger self, who recoiled from comparisons to my mother, today I own my mother’s influence with pride.

Through my adolescence and right up into my ‘50’s, I balked if anyone told me that I looked like my mother, talked like her, or resembled her in any number of ways. I was the consummate rebel daughter, picking fights with my mother at the drop of a hat. Fundamentally I was angry with her for not standing up to my father who dominated her, for not showing me how to be an independent woman. My subconscious bells signaled if I resembled my mother, I might end up like her, ruled by a tyrannical husband.

In the late ‘60’s when I attended a graduate social work program mother blame was in fashion, pointing the finger at mothers for their children’s problems.

To this day mother blame remains embedded in white culture. For decades mother-daughter tensions have fueled the self-help industry. Does patriarchy foster the mother-daughter divide? Does this conflict, which can dominate a woman’s entire life, box her in and suck away her power?

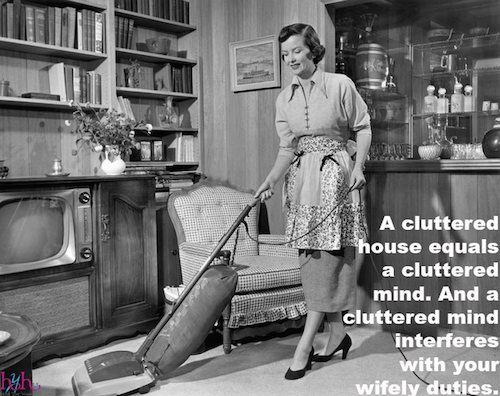

My mother anger softened as I immersed myself in feminist theory. It opened my eyes to the ways my mother’s generation was programmed to be a wife and mother, essentially to be selfless in the service of others. Growing up I barely remember my mother sitting down. She was constantly cooking, cleaning, doing laundry, entertaining for my father’s cronies and chauffeuring her kids to after-school programs.

An example of 1950’s messaging designed to make women of my mother’s generation feel that homemaking was their rightful role

As I talked feminism with my mother, she began to make changes. She joined the Planned Parenthood board, taking on her conservative friends by championing abortion rights. I was proud of her even though she still deferred to my father.

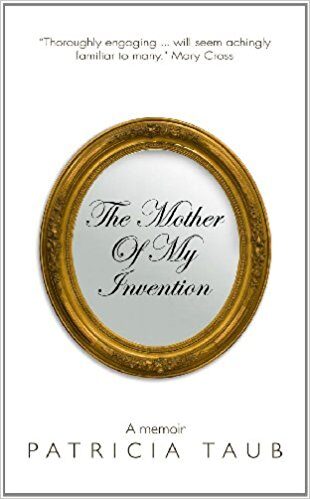

It wasn’t until my mother died and I wrote a memoir about our relationship that my healing felt complete. I stopped blaming my mother for my imperfections. I learned to see my mother’s life through her eyes, recognizing that she had an uphill fight in a very misogynist culture.

I believe that whenever a woman fails to make peace with her mother, the mother line is severed in ways that affect us all. The more mother wounds individual women can heal, the more we all heal. The more we can collectively embrace the internalized good mother while working to heal the internalized damaged mother, the more we can own our power.

This is a loving path far preferable to a lifetime of mother complaints, which sends negative mother energy into the universe, contaminating all those women in its sphere.

White women can turn to other cultures for examples of honoring the mother line. Rather than obsess over their mother wounds, Native American women honor their mother line, paying homage to the contributions of their female elders. One ritual practiced by many Native American tribes is the “honor dance” performed on Mother’s Day. Women of all ages dress up in elaborate traditional clothes while their community dances to honor their role as mothers and elders—a more meaningful tradition than bestowing flowers and candy on mom!

In the book, Toni Morrison and Motherhood: A Politics of the Heart, contemporary African American women’s writing is noted for its tendency to celebrate mothers as mentors and role models and the power daughters have in connection with their mothers and the mother line.

Today courageous mothers and women across the globe are raising their voices as they mount protests for racial and economic justice, a Green New Deal, and female equality. Women are becoming a viable political force. We are making our foremothers proud!