This post was originally printed in “Popular Resistance,” November 5. 2013. I’ve reposted it in response to the demonstrations at Standing Rock, which have a strong spiritual basis. I dedicate this post to the brave Native Americans at Standing Rock, the “water protectors.”

I’ve been an activist for my entire adult life, working tirelessly for peace and progressive causes. As a graduate student I protested the Viet Nam war, and later took up the charge for women’s equality and civil rights. If someone questioned my motives, I didn’t think very deeply about why I protested. I simply said that I wanted to make the world more equitable.

But about ten years ago, as my spiritual practices deepened, I came to regard activism as interconnected with the sacred. The more I see activism in this light, the more of a moral imperative it becomes for me to protest.

While I’m still wrestling with the concept of God, even after spending time in a women’s retreat center, I’m clear about my attachment to peace and social justice as necessary components for manifesting the sacred in the world.

A book promo for “Occupy Spiritually” with the authors, Adam Bucko and Matthew Fox

Regarding activism as sacred has broadened my perspective, making compassion and a respect for differences central in my thinking. In this respect I’ve been influenced by liberation theology as advanced by Matthew Fox, a defrocked Jesuit Priest. Fox cautions activists, “If we’re only acting out of anger, we reproduce the energy and momentum of destruction.” (I don’t think Fox is negating righteous indignation, which is a wake-up call for many causes, but warning against a calcified angry stance.)

Fox regards community building as a soulful enterprise:

We want to remember, over and over again, how our destinies are woven together. We want a spirituality that holds the liberation of all people at the center . . . The organizing principles of collective liberation encourage authenticity and disagreement. We embrace conflict as a powerful tool for learning and growth.

Implicit in Fox’s writing is the challenge for progressives to find common ground with seemingly opposing groups, like the Tea Party, which favors grass-roots movement building on the order of Occupy, or the Libertarians, who, like progressives are opposed to the excesses of the NSA, drone warfare and preemptive US military strikes.

Clergy from Occupy Faith, marching with the Occupy Movement of 2011

A compassionate outlooks leads to non-violent resistance as practiced by Gandhi and Martin Luther King and advocated by Gene Sharp, a Boston area intellectual and founder of the Albert Einstein Institute, a nonprofit institute devoted to the study of nonviolent resistance.

Sharp’s book, “From Dictatorship to Democracy” became the bible for the Arab Spring, promoting nonviolence as the only effective way to bring about change. Sharp believes that when movements turn violent, they lose because they invite military action. America’s history of violence presents a challenge to all nonviolent protestors.

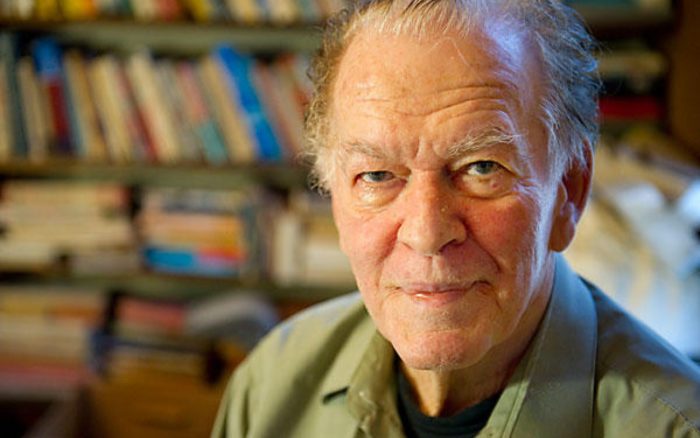

Gene Sharp, author of “From Dictatorship to Democracy,” a guidebook for the “Arab Spring”

Andrew Harvey, a New Age thinker, who promotes “sacred activism,” encourages everyone to ask himself or herself, “What is sacred to me?” and then to act on this response. For example, many people regard caring for the planet as sacred.

Sister Louise Akers

Sister Louise Akers, who in a manner similar to Matthew Fox, was stripped of her teaching position for speaking out against the Catholic Church’s inattention to the needs of the poor and for their opposition to women’s rights, regards social activism as the ultimate transformative experience, believing that when she works to help transform the lives of the poor she is transformed as well. What could be more sacred?