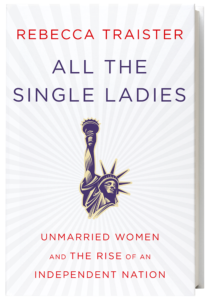

I spent last weekend glued to the nonfiction best seller, All the Single Ladies, a brilliant Feminist study by Rebecca Traister. It deconstructs how single women from Civil War heroines like Clara Barton to leading Suffragettes to today’s young women in their 20’s and 30’s have delayed or rejected marriage in order to escape its restrictions on personal achievement.

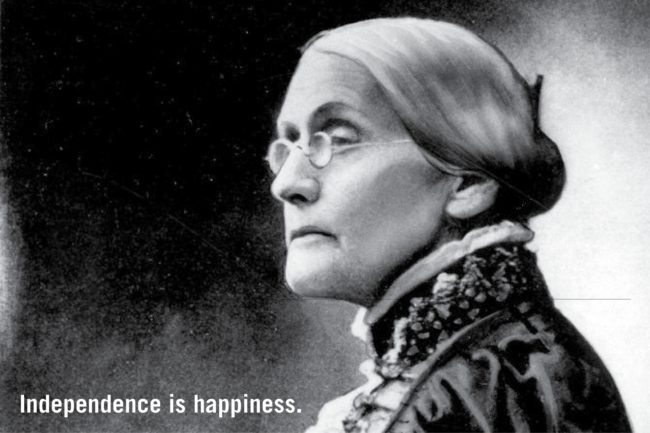

The famous Suffragette, Susan B Anthony, an early marriage resister

Traister examines the traditional path of marriage for women, claiming it was virtually their only way to obtain economic security and social status. Once married, all dreams of personal fulfillment were swept under the rug in favor of childcare and domestic chores. Wives were little more than indentured servants to husbands who had the freedom to work and move about at will in the outside world.

Marriage was America’s patriarchal glue.

A 1950’s housewife looking radiant in spite of her marital bondage

Reading Traister’s book reminded me how my mother would put down my father’s “maiden aunts” (A generation older than her!) who lived together, pursuing their respective careers as a hat designer and government clerk, having turned down marriage offers. My great aunts were not the social failures the family whispered about. Instead they were living the lives they wanted, happy in their careers and travels. I think my mother was secretly envious of their life style. Like many widows of her generation, who had succumbed to her husband’s every wish, my mother blossomed after my father died, finally able to create a life on her terms.

Young single career women engaged in networking

The subtitle to Traister’s book is “Unmarried women and the Rise of An Independent Nation.” This is where she breaks new ground. She credits the new breed of single women who defer marriage responsible for increasing female options.

Women now own their own homes, travel and dine solo, start their own businesses and even have babies on their own. For the first time in history a woman can be complete outside of marriage.

And there’s the rub. When Traister identifies the lack of social supports available to single women she ventures into class and racial inequalities. She notes the enormous struggles facing poor single women, who form the bulk of minimum wage workers where the current minimum wage is not a living wage. I wish she had spent more time addressing the concerns of minority women, but, she stayed largely with what she knew, interviewing privileged white women like herself. She notes that there are tensions that affect single mothers of all classes. Chief among these are the need for government-subsidized childcare, paid maternity leave, and expansion of medical benefits for single mothers and their children.

A single Black mother, lacking Traister’s privileges, in need of government funded daycare.

In the course of writing this book, Traister fell in love, married at age 35 and subsequently had two children. She implies that the confidence she developed during her years as a singleton, as with her peers who married late in life, has helped to create greater marriage equality in childcare and domestic responsibilities.

I believe that the growing number of older women, divorced, widowed, or never married, who tell me, “I wouldn’t have a partner for anything,” represent a late-in-life freedom in being single.

Stay tuned: future blogs will feature interviews with older women content living alone.

If you’d like more conversations with like=minded women, we have a Facebook page for you: WOW (Women’s Older Wisdom)